The Sanskrit language lends itself to choice of words that can create an interplay between sounds and meaning. Every language has unique cultural references and conventions built into it. Sanskrit has long tradition of associated cultures that evolved from the ancient Vedic right up to the late medieval.

A translation has a certain readership in mind that belongs to a certain cultural milieu. This readership by all means has different expectations out of literature. Yet this readership may be open to variety and innovation that can arise out of alien modes of expression. It would therefore be unfair and unproductive to put the translation entirely into the strait-jacket of contemporary conventions.

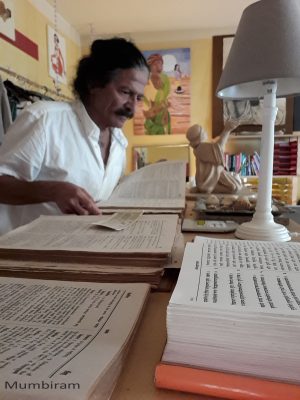

A translator of Sanskrit compositions that are simultaneously about love and spirituality into contemporary English prose of a comparably youthful, emotional, vibrant, spontaneous and sensitive generation has indeed a daunting task ahead. The translator must be equally adept in the cultural milieu and idiom of expression of the two civilizations he is attempting to connect.

Yet love and spirituality are universal and timeless. They are perceived, comprehended and practiced in remarkably identical ways going beyond the temporal and cultural. Bringing out this congruence across the language-divide is the challenge as well as joy of the translator’s endeavour.

All four classics translated in “High Five of Love” are descriptions of the conjugal sporting of the adolescent Krishna entering into Manhood. Yet they span a long period of time in their dates of creation. Besides, they are each of a different literary genre. Vyasa´s “Five Songs of Rasa” are verses in the epic category. Jayadeva´s “Conjugal Fountainhead” is nearly an opera. Vishvanath Chakravarti´s “Jewel-Box of True Love” is an episode with an ingenious plot howsoever profound. In contrast “Vrindavan Diaries” is fast moving incessant colloquial prose in the guileless tongue of village-damsels who wouldn’t dream of ever leaving their fair Vrindavan.

These translations have more than lived up to the challenge of conjuring up appropriate linguistic aura for these different classics.

There are certain subtle states of consciousness that are acknowledged by the popular culture associated with a language. These have a word in that language. Mere mention of that word conjures up a gamut of associated emotions. Other languages that don’t have such a word will struggle to achieve that same expression. Take the word leela. It refers to activities that one performs entirely out of one’s own sweet will rather than out of a sense of duty or helplessness. It implies total ease and a sense of wonder. There exists no word in the English language that renders the same meaning. Translators have used “sporting activities” which is quite inadequate. We can clearly foresee “leela” entering popular English usage just as “avatar” already has. The French word déjà vu is another example. English language has already adopted it. Everyone that knows Sanskrit or one of its derivative Indian languages is familiar with the ecstatic symptom “romaancha”. The English equivalents “hair standing on end” or “goose-bumps” are too clinical. “Hair-raising” is simply horrible. Sanskrit “rasa” is another example. Thus far English has had to make do with “transcendental mellows” which leaves it quite vague for all those who are unfamiliar with Sanskrit.

These translations of Sanskrit classics are a “juicy” introduction, for the entire English reading fraternity, to all that the word “rasa” conjures up.